The killing of Osama bin Laden in 2011 has become a highly charged political issue in the 2012 presidential election. President Obama has taken the credit away from the “doers of the deed”, our military, who put their lives on the line. The Executive Order (ExOrd) to kill Osama bin Laden didn’t take “guts”, just a good decision by the commander in chief.

An ExOrd is a powerful tool for the President to be used to protect the American people. Once issued for a military action, whether the mission is successful or not, credit should be given to the military for their efforts in taking the risk. In the event the mission fails, the commander in chief accepts the full responsibility.

President Harry Truman succinctly stated in his farewell address to the American people in January 1953 that “The President–whoever he is–has to decide. He can’t pass the buck to anybody. No one else can do the deciding for him. That’s his job”.

Research for my book, “When the White House Calls” indicated that we had Osama bin Laden in our “crosshairs” as far back as the mid 1990′s. President Clinton reportedly had several opportunities to capture or kill Osama bin Laden, but did not have the “will” to issue the ExOrd for this mission. Sudan’s President al-Bashir also offered to have Osama bin Laden extradited to the United States in 1996, which President Clinton turned down.

We could have learned a lesson from the terrorist style of fighting in the early 1980s, when there were thirty-six suicide attacks against Americans and others inside Lebanon; including Hezbollah’s bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut on April 18, 1983, which killed sixty-three people.

In 1982, the Lebanese government requested that the United States establish a peacekeeping force to control conflict between Muslims and Christians. The Muslim military forces viewed our soldiers as their enemies and attacked them regularly.

On October 23, 1983, truck bombs struck two buildings housing U.S. and French troops, part of the multinational force. In the attack on the American barracks, 241 American servicemen were killed; the French lost fifty-eight of their military personnel. The Islamic Jihad took responsibility for the bombings on this occasion.

Then on December 12, 1983, a truck filled with gas cylinders and explosives rammed into a three-story administrative wing of the U.S. Embassy in Kuwait City, killing five people. That attack was undertaken by a radical Shi’ite Islamic group with ties to Iran.

We were not prepared to prevent these attacks, or to deal with this new enemy, a fundamentalist Islamic movement bent on the destruction of the United States.

We need to remember the words of Osama bin Laden when he referred to the American troops coming to Saudi Arabia in 1990 as infidels occupying Muslim soil and declared a jihad against the U.S. He didn’t want any foreign troops on their sacred soil, “in the land of the two mosques, Mecca and Medina”.

In a March 1997 CNN interview, Osama bin Laden stated, “In our religion, it is not permissible for any non-Muslim to stay in our country.” A similar message had come several years earlier from radical Muslims in Beirut who did not want American troops on their soil and attacked our soldiers.

Beginning in 1991 we had sound intelligence information on the whereabouts of Osama bin Laden, and his al-Qaeda leaders including Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, all of whom had been given safe haven in Sudan; along with other radical Islamic groups. Many of the terrorist attacks were planned by bin Laden while in Sudan.

In 1996 President Clinton pressured Sudan to expel Osama bin Laden to Afghanistan, instead of having him extradited to the United States. With him went some of the most dangerous terrorists, including Ayman Zawahiri the chief planner for the September 11, 2001 attacks, Mamdouh Mahmud Salim an electronics expert; Wadih el-Hage, Fazul Abdullah Mohammed and Saif Adel who were all involved in the August 1998 bombing of two U.S. embassies. Two of the terrorists who trained in Sudan were also involved in the September 11, 2001 attacks.

The CIA had full knowledge of the terrorist connections with different attacks against U.S. interests around the world. We could have captured Osama bin Laden at the time. According to reports President Clinton didn’t have the “will” to give the Executive Order (ExOrd) in 1996 to carry out such a mission.

The United States had had many warnings from the Comoros government that large numbers of foreigners and radical Islamic clerics were traveling to and from the Comoros islands in the 1990′s. The government at the time was concerned about the potential threats these strangers posed from this influx, and wanted our help—but we did not respond.

Fazul Abdullah Mohammed was born on the island of Grand Comore, and lived in Moroni the capital. Like many other young children, he attended madrassas, (Koranic schools). Fazul was recruited by Islamic imams (preachers) to study in Pakistan. Ostensibly, his family had sent him to study computer science, but ultimately he made his way instead to Afghanistan to train with Osama bin Laden. Fazul then went to Kenya, with occasional trips to Tanzania and Somalia to help train and establish terrorist cells.

The U.S. Embassy in Comoros was closed in 1993, “as an area that had little interest to the United States”. Hence we lost further in-country intelligence information. The State Department and other agencies did not believe there were any infiltration concerns with terrorist groups in Comoros. For radical jihadists such as Fazul Abdullah Mohammed the islands in the Indian Ocean had become a safe sanctuary.

Fazul was the mastermind of the 1998 bombings of the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi, Kenya, and the U.S. Embassy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He was also involved in the November 2002 bombing of the Israeli-owned Paradise Hotel in Kikambala, a beach resort fifteen miles north of Mombasa in southeastern Kenya, and the attempted surface-to-air missile attack on a Boeing 757. He was also implicated in the smuggling and sell of blood diamonds from the West African country of Sierra Leone, the proceeds of which are believed to have been a major source of funding for the 9/11 attacks.

After the U.S. embassy bombings, Fazul returned to Comoros on August 14, 1998 to hide out with his family. While there he visited the school in Moroni where his brother was a teacher. A former classmate ran into him, but at first did not recognize him. This person later related the story of when Fazul was thirteen or fourteen years old and constructed a homemade bomb, which he detonated in front of his friends at school.

In Moroni no one knew Fazul had anything to do with the embassy bombings. Even when the FBI came to the island, no one knew who or what they were pursuing until sometime later. Fazul could have easily been captured, since the government of Comoros had invited the FBI to come to the island to apprehend him. By the time the FBI had responded three weeks later Fazul had already fled the country.

Between 2000 and 2001, a local judge in Moroni assigned to the Fazul case, gleaned information that he was periodically speaking to his wife Halima on a neighbor’s telephone. There was no structure put in place by the United States for intelligence gathering. If we had an active diplomatic presence in Comoros at the time, the FBI and other agencies could have taken timely action, possibly leading to the capture of Fazul.

In March 2003, the U.S. Embassy in Mauritius received information from the regional security officer at the U.S. Embassy in Antananarivo, alleging that al-Qaeda operatives were moving through Comoros. As many as two hundred foreigners were in Mohoro, a small village on Grande Comore, staying in mosques and madrassas. This information was validated by reports we had received from other sources.

Information reached us that Fazul had plans to visit Comoros for a family funeral, and then a trip to Mahajanga, a town on the northwest coast of Madagascar (a short boat ride from Comoros).

On another occasion an anonymous email reached the embassy, from a Comorian source saying that a Pakistani was departing Comoros the following Sunday en route to Pakistan to make contact with Fazul. This individual sold cellphones, tapes, cassettes, watches and so on, and traveled to Comoros every three weeks, carrying correspondence from Fazul to family members. The source commented that various people from Madagascar frequently met with the Pakistani in Comoros. He said Fazul was in Pakistan in an area where he wouldn’t have any problems.

All this information on Fazul Abdullah Mohammed’s whereabouts and travel plans was passed on to Washington, but we never heard back.

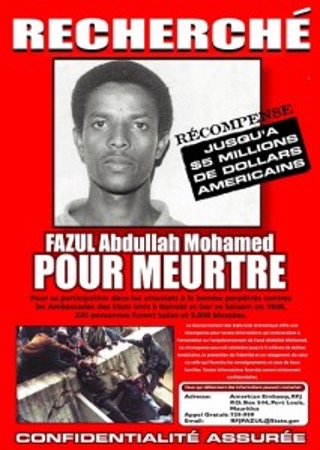

We subsequently pressed our embassy regional security officer to obtain funding for the “Rewards for Justice” program. Large posters were prepared of Fazul with a photo of the bombed out embassies, which were attached to telephone poles and placed inside shop windows around Grand Comore. Boldly printed was a $5 million reward for information leading to his capture. Comorians are a close-knit Arab Muslim society, so odds were they would not turn him in. In addition there was skepticism about the United States actually paying this amount to anyone.

Wanted poster for Fazul Abdullah Mohammed Issued by the Rewards for Justice ProgramThe U.S. needed to maintain a presence in Comoros, to build a relationship of trust. Dealing long distance would lead to a less than desirable result. With many Comorians living along the east coast of Africa and on the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba some of these people could have been recruited to track Fazul. We also needed to have some money ready in exchange for information. More importantly we needed to have an active presence throughout the region, to develop friends, and build a lasting trust. But this did not seem to be a priority for the United States.

Wanted poster for Fazul Abdullah Mohammed Issued by the Rewards for Justice ProgramThe U.S. needed to maintain a presence in Comoros, to build a relationship of trust. Dealing long distance would lead to a less than desirable result. With many Comorians living along the east coast of Africa and on the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba some of these people could have been recruited to track Fazul. We also needed to have some money ready in exchange for information. More importantly we needed to have an active presence throughout the region, to develop friends, and build a lasting trust. But this did not seem to be a priority for the United States.

It was reported that Fazul spent considerable time in Lamu, Kenya, and in an al-Qaeda training camp near Ras Kamboni in southern Somalia. U.S. intelligence sources indicated that Islamic extremists were harboring the senior al-Qaeda leaders—Abu Talha al-Sudani, Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, and Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan—all reportedly responsible for the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassy in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam.

Pursued by Transitional Federal Government (TFG) and Ethiopian troops the Battle of Ras Kamboni against these insurgents began on January 5, 2007. That same morning, a jihadist website sent out a message from al-Qaeda’s second-in- command Ayaman al-Zawahiri urging Muslim brothers to “rise up and support your brothers in Somalia.” The following day two U.S. AC-130 gunships, originating from our military base in Djibouti, flew to a small airport in eastern Ethiopia, serving as a staging area. The U.S. Special Ops Forces and Kenyan troops had positioned themselves on the Kenyan border preparing to capture any fleeing Islamist fighters and al-Qaeda leaders. Early on January 7, the AC-130 gunships proceeded down to Ras Kamboni and carried out air strikes against the Islamist fighters, and suspected al-Qaeda leaders embedded with them.

The next day, AC-130 gunships attacked another suspected al-Qaeda camp. Ethiopian helicopters and an AC-130 struck Islamist fighters in yet another suspected area. Three days later, conflicting reports were issued regarding the success of these air attacks. News reports indicated Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, one of the most wanted al-Qaeda terrorists had been killed. Several days later a news release came from the State Department, stating that the attacks had failed to kill Fazul.

Reports however did claim that at least thirty-one civilians died in the assault. These air strikes against civilians caused an international outcry aimed mostly against the United States. Although witnesses in one of the attacks described what turned out to be the Ethiopian helicopters in that attack. These were the first such airstrike operations within Somalia since October 3–4, 1993, when U.S. and UN troops were involved in a military battle in Mogadishu, in which we lost eighteen U.S. soldiers and two helicopters; with many other soldiers wounded.

Since the January 2007 military action fighting between the TFG and UN troops and Islamic insurgents has continued in Mogadishu, and other areas of southern Somalia. There have been a number of car bombings and other terrorist-type disruptions—all signs of an al-Qaeda presence—but no sign of Fazul.

On June 2, 2007 the destroyer USS Chafee fired its heavy guns into a remote northern coastline area of Somalia where reportedly several Islamist fighters were embedded. It was later disclosed one of the targets was Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, thought to be hiding in this isolated area.

On April 14, 2008, in a Center for Strategic and International Studies article “Comoros: Big Troubles on Some Small Islands” Matthew B. Dwyer, a former Peace Corps volunteer who served in Comoros in the 1990′s wrote, “The United States has a clear interest in preventing the Comoros from becoming an attractive place of refuge for wanted terrorists such as Fazul”, and that “The Comorian government is on record as being eager to cooperate with U.S. and UN anti-terrorist efforts”. Dwyer expressed concerns about the need to have a permanent U.S. presence stating, “In the Comoros the United States has committed only sins of omission. This must change, and the first step should be the reinstatement of the U.S. Embassy to the Union of the Comoros. It is no coincidence that the most peaceful period of Comorian independence coincides with the presence of a full U.S. diplomatic mission in the islands. It is time for Comorian[s] to once again be able to count the United States as a friend”.

During a meeting with a Comorian government leader in 2009, he shared information about Fazul’s wife Halima receiving a new electronic-type passport (e-passport) from the Comorian Department of National Security. The government of Comoros had not stopped the issuance of the passport, and the U.S. took no action. We had not advised the Comorian government to watch her movements, or prevent her from getting such a passport, which would open the world to her.

Soon thereafter Halima flew to Anjouan, sailed to Mahajanga and went on to Antananarivo. There she boarded a plane to Nairobi, and then crossed the porous border into Somalia. Her purpose was to attend the installation of Fazul as the new leader of Somalia’s al-Shabaab organization. Nobody had followed her, or checked her sources of money to make this trip.

Al Shabaab fighters active in northern Mogadishu (Photo: Christian Science Monitor- Farah Abdi Warsameh/AP/File)Al-Shabaab is the outgrowth of the Islamic Courts Union. This Islamic insurgent group was intent on starting a holy war against Christians in Ethiopia, the Somali Transitional Federal Government (TFG), the African Union (AU) peacekeepers, and western NGOs in Somalia on humanitarian missions.

Al Shabaab fighters active in northern Mogadishu (Photo: Christian Science Monitor- Farah Abdi Warsameh/AP/File)Al-Shabaab is the outgrowth of the Islamic Courts Union. This Islamic insurgent group was intent on starting a holy war against Christians in Ethiopia, the Somali Transitional Federal Government (TFG), the African Union (AU) peacekeepers, and western NGOs in Somalia on humanitarian missions.

Under Fazul’s leadership terrorist activities were expanded to include the use of car bombs, suicide attacks, road mines, and other disruptive bomb attacks in densely populated areas. Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, once considered a man of no consequence by our government, had risen to the ranks of Osama bin Laden’s inner circle, a close lieutenant, and leader of al-Qaeda in East Africa. Now as the leader of al-Shabaab also, he could no longer be ignored.

On June 8, 2011 Fazul was traveling from South Africa to Somalia, and was met by a trusted associate at a border crossing area. Returning to the al-Shabaab controlled section of Mogadishu, at a checkpoint they ran into TFG and AU military troops. In the ensuing fire-fight Fazul and his associate were killed– for which the world is safer.

However, had we issued the Executive Order to capture Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda leadership while in Sudan in 1996, before declaring his “fatwa” against the United States, the destructive terrorist acts that followed could have been avoided. For fifteen years the world has lived in fear; we have spent an inordinate amount of resources to locate and kill bin Laden in 2011. The world would ha