“Africa Has a History of Irrational Borders”

(Excerpts from When the White House Calls, and February 8, 2012 Commentary, Sudan- Erratic Diplomacy at Best)

In the seventh-century Arab traders sailed into the various ports along the coastline of the Horn of Africa and East Africa for refueling, gathering supplies, and selling wares. Gradual colonization of sub-Saharan Africa followed with early European traders who secured coastal enclaves as a base of operations for their trade activities. Ultimately, the British, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish, Belgian, and Italian colonizers established port settlements ringing the entire African continent. It wasn’t until the late 1880s that these colonizers journeyed farther into the vast interior of the African continent, grabbed land, and created settlements, dislocating local tribes along the way. This rapacious land rush led to the 1885 Berlin Conference that established guidelines for the acquisition of African territory. Within a thirty-year period, by 1914, the African continent was carved up by these European powers.

For more than fifty years, while Sudan was under British and Egyptian rule, little thought was given to the vast tribal, ethnic, and religious distinctions; cultural and social differences or historical boundaries. Defined by the colonialists, Sudan’s boundaries were geographically based. Muslim Arabs lived in the northern areas and Christian Africans and animist tribes occupied the southern areas. In the western Darfur region, more than eighty tribes composed of farmers who were predominantly black Africans with Muslim beliefs and nomads who were of primarily Arabic descent. In February 1953, Sudan signed an agreement with both Britain and Egypt providing its own government and self-determination that led to its independence on January 1, 1956. But the country’s inherent problems were deep-rooted and many.

In Sudan the contentious geographic boundaries had scarred the country, its government was splintered, and its people were left with a legacy of tribal and ethnic conflicts. Moreover, no sooner was the ink dry than the Sudanese government broke its many promises to the south, inciting much bloodshed, genocide, and instability. Civil war and military uprisings took over the country and raged on for nearly twenty years—a ruthless bloodbath in which more than two million people were killed. In 1972, peaceful coexistence seemed possible when the Arab-speaking Muslims in the north made a commitment to the predominantly English-speaking African Christians in the south that they would create a federal system allowing for autonomy in the southern region. The Addis Ababa Agreement was brokered offering compromises and a degree of self-rule in the south that led to a status quo for a period of ten years.

In the 1950s, fighting for independence from the colonialists became endemic, and by the 1970s, most African countries had gained their independence. However the European colonizers left behind irrational borders, which ultimately lead to conflict and chaos in these countries. In Sudan, civil war and strife have caused a debilitating agricultural and economic catastrophe that further eroded the country’s stability. Outside investments dwindled. Food shortages caused by agricultural neglect, the lack of education, limited healthcare, and unemployment affected both the north and south. In the south alone, almost four million people were forced to flee to neighboring countries. In 1982, civil war was again ignited, exacerbated by the Sudanese government’s Islamic policies toward the south, and seven years later the National Islamic Front came to power with the intention of building an Islamic state.

Radical Islamists from around the world were given free rein and safe haven—a lead that would soon be taken by Osama bin Laden, who, having left Afghanistan had worn out his welcome in his home country of Saudi Arabia. Arriving in 1991, he stayed as a guest of the Sudanese government until the U.S. asked for his expulsion from Sudan in May 1996, ending up back in Afghanistan.

In the early 1990s, when CIA intelligence information of possible terrorist attacks was released, the State Department placed Sudan on its list of states sponsoring terrorism, and the U.S. embassy in Khartoum was closed for short periods of time. Increased threats against the U.S. presence reportedly caused the withdrawal of U.S. business interests and some of our diplomatic presence. Then, in 1996, the United States pulled out all our diplomatic presence including our intelligence resources, and the U.S. embassy in Khartoum was shuttered on February 7, 1996.

Thus we lost access to all opportunities to secure further credible in-country intelligence and had to rely instead on exiles, political factions, and sources in neighboring countries, as well as questionable CIA contacts. Without U.S. embassy representation, we had a vacuous picture of what was happening inside Sudan. The United States then became more dependent upon paid information.

The full withdrawal of the embassy personnel was based on CIA intelligence reports. Only later did we learn that before the withdrawal, the CIA in 1995 had realized it had faulty intelligence reports based on claims revealed to have been fabricated. However, all operations at that point had been transferred to the U.S. embassy in Nairobi. It wasn’t until seven years later in 2003 that the U.S. embassy in Khartoum reopened with limited resources, headed by a chargé d’affaires. Although there have been a number of U.S. Special Envoys for Sudan, the effect has been nominal, since they were there for short periods of time. It was erratic diplomacy at best. To successfully engage Sudan and be effective, we needed to be there with a full time diplomat—an accredited U.S. ambassador.

In the Horn of Africa, Sudan is considered a failing state. The country with a significant Muslim and Christian population, has had internal strife, inter-clan fighting, safe-havens for terrorist groups and terrorist training camps; participated in genocide – all of which have become the norm ever since. Peace negotiations have been persistent, but progress is measured only by optimism at times, rather than substantive lasting solutions. With the signing of the 2005 Peace Agreement, heralded by many, CNN noted on January 9, 2005, Historic Sudan peace accord signed: “After nearly three years of negotiations, Sudan’s government and main rebel group Sunday have signed comprehensive peace accords to end more than 21 years of civil war”.

In January 2011, a self-determination referendum vote was held in southern Sudan as provided for in the peace accord, between the Khartoum government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement. On February 7, the results were announced with the majority of the people voting in favor of independence. The Republic of South Sudan officially became an independent state on July 9, 2011. However the border between both countries was never totally defined at the time, so a further referendum vote, which would include the oil-rich Abyei region still needed to be held. The partitioning of Sudan was the only viable solution to resolve the ethnic differences between the Muslim north and Christian south, with each of these societies being given their own homeland as sovereign states.

Since the oil resources are mostly located in the Christian south, this economic obstacle should have been addressed, with a fair revenue sharing arrangement, at the time of the 2005 peace agreement negotiations. The United States was a key broker in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). The accord provided for an undefined, irrational border, which was no better than the colonialist legacy of the 1950′s. We were willing to accept two independent countries without fixed borders.

To further complicate matters, the U.S. had wanted to remove Sudan’s President Omar Hassan Ahmed al-Bashir, have him arrested, and sent to the International Criminal Court in The Hague to face charges of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. According to Stephanie McCrummen and Colum Lynch’s December 8, 2008, New York Times article, Sudan’s Leaders Brace for U.S. Shift, political science professor in Khartoum and ruling party lawmaker Saswat Fanous warned, “Any destabilization of this government and all these Islamist elements will certainly turn into a dangerous force. They will be driven underground, and they will invite in a flood of radical Islamists coming from the region into Sudan.”

Food is one of the main worries for the displaced (Photo: Hannah McNeish/IRIN)In the IRIN News Africa article of April 10, 2012, SUDAN-SOUTH SUDAN: Abyei displaced struggle to survive in impoverished villages, Amou Manyuol noted, “Sudan’s occupation prompted more than 100,000 Ngok Dinka, the region’s main permanent residents, to flee southwards. Sudanese troops remain in Abyei, despite a September agreement for them to leave”. [S]he wanted to go back to Abyei, “where there used to be enough clean water and food for everyone, despite the fact that she lost three brothers there”, saying “Life in Abyei before was good…now depending on relief as some of the hundreds of other women waiting for food distributions crowded around nodding their assent”.

Food is one of the main worries for the displaced (Photo: Hannah McNeish/IRIN)In the IRIN News Africa article of April 10, 2012, SUDAN-SOUTH SUDAN: Abyei displaced struggle to survive in impoverished villages, Amou Manyuol noted, “Sudan’s occupation prompted more than 100,000 Ngok Dinka, the region’s main permanent residents, to flee southwards. Sudanese troops remain in Abyei, despite a September agreement for them to leave”. [S]he wanted to go back to Abyei, “where there used to be enough clean water and food for everyone, despite the fact that she lost three brothers there”, saying “Life in Abyei before was good…now depending on relief as some of the hundreds of other women waiting for food distributions crowded around nodding their assent”.

Fighting and chaos has continued between Sudan and South Sudan armies and some rebel militia forces. To add to this instability there has been tribal fighting, and rustling of large herds of cattle the main stay for several of the tribes bridging the land areas. “Attacks and counterattacks that involve members of the Murle and Nuer tribes have spiked in the last 12 months, though the bad blood goes back for generations and originated in the practice of cattle raiding”, was noted in the March 12, 2012 Los Angeles Times article, Scores dead in a new bout of South Sudan tribal violence, adding “Some 120,000 people have been displaced in the recent attacks in Jonglei state.”

Residents fleeing the violence in South Sudan (International Medical Corps Photo)

Residents fleeing the violence in South Sudan (International Medical Corps Photo)

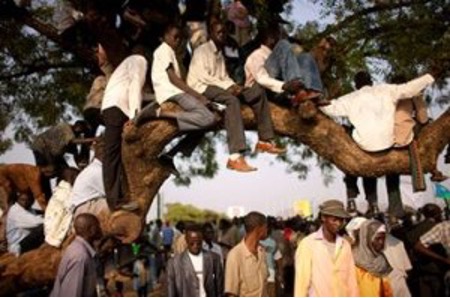

South Sudanese at the formal declaration of independence in the capital city, Juba on July 9, 2011. (Pete Muller / AP)

South Sudanese at the formal declaration of independence in the capital city, Juba on July 9, 2011. (Pete Muller / AP)

“Disarmament must be thoroughly carried out in all the areas of south Sudan. Security needs to be tightened along the borders, particularly the north-south border”, as noted in the Hub Pages article by Mokswilly, The Ordeals of Walking Behind Cattle in Jonglei State. The on-going instability in the southern region has brought about a new humanitarian crisis.

In the Associated Press article by Tom Odula on April 21, 2012, Obama to Sudan and S. Sudan: War is not inevitable, negotiations key to lasting peace, President Obama stated, “Sudan and South Sudan have been drawing closer to a full scale war in recent months over the unresolved issues of sharing oil revenues and a disputed border. The disputes began even before the south seceded from the north in July 2011. The South’s secession was part of a 2005 peace treaty which ended decades of war that killed 2 million people.” The partitioning was to resolve the long standing disputes between the ethnically different regions. As noted, the colonial powers irrational borders established at independence, have affected many of the African countries, creating a long history of civil strife throughout the continent.

Peace and security for Sudan and South Sudan, cannot be achieved without properly defined borders; which need to take into account ethnic cultures and tribal homelands. For a long lasting peace, both sides need to agree on a fair revenue sharing arrangement over the oil resources. “Geologic oil formations have no geographic boundaries, and most likely exist under both sides of the border demarcation line.”