“Al-Qaeda has been working hard to gain a foothold in every country that has a significant Muslim population, and to destabilize the region, and attack Western interests. The attacks on September 11, 2012 were well planned and executed. To believe they were spontaneous is beyond naïve”

The White House does not want to recognize that there is still a Global War on Terror (GWOT). So I am not surprised at the politicized remarks by the State Department and our U.S. ambassador to the UN, that the attacks on the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi on September 11, 2012 were a spontaneous act. The video Innocence of Muslims may have been a contributing factor to demonstrations that took place across North Africa, but the attacks in Benghazi were undertaken by al-Qaeda linked terrorists, in their hatred for the United States. In the attacks we lost Ambassador Chris Stevens, and three other embassy officials.

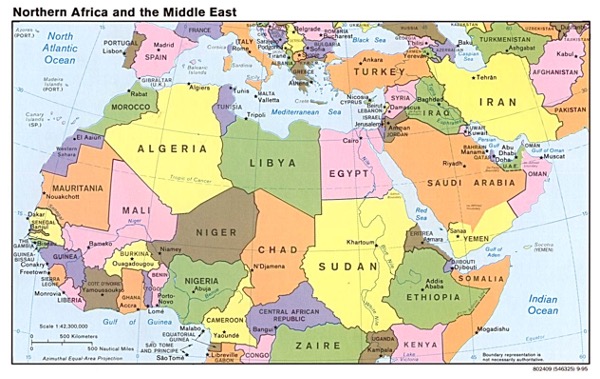

Salafist and Wahhabist imams used the video to stir up the emotions of predominantly young men, living in a vacuous society of unemployment, high food prices, lack of education, and anger against the West. As the fateful events unfolded in Benghazi, I was returning from the Mintao Refugee Camp in Burkina Faso, where I met with several Tuareg and Arab elders from northern Mali. The region had been overrun by Tuareg rebels associated with the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) and Ansar Dine Islamists. The more nascent Tuareg rebels have since been pushed aside. Ansar Dine has now associated with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) from Algeria, Boko Haram from Nigeria, and al-Shabaab from Somalia. These groups are embedded across the vast Sahel. Afghan and Pakistani jihadists have also infiltrated Mali, and are training recruits, the latest sign that the region is slipping into terrorist hands.

During the Arab Spring uprising in Libya, several rebel militia groups became affiliated with al-Qaeda, including Ansar al-Sharia and the Libyan Islamic Front; other Islamists were interwoven in a rag-tag association. Mali, a fledgling democracy, was destabilized after the downfall of Muammar Gadhafi, when enlisted Tuareg fighters returned home, bringing with them a large cache of arms which fell into the hands of radical Islamists. Similar weapons are in the hands of al-Qaeda and rebel militias in Benghazi, and were used in the attacks on the U.S. Consulate.

We could have learned a lesson from terrorist style attacks back in the early 1980s, when there were thirty-six suicide attacks against Americans inside Lebanon, including Hezbollah’s bombing of the U.S. embassy in Beirut in April 1983, which killed sixty-three people. The government had requested the U.S. to send a peacekeeping force to control the conflict between Muslims and Christians—our troops however were viewed as the enemy of the Muslim military, and were attacked regularly. In October 1983 truck bombs struck two buildings housing U.S. and French troops. In the attack 241 American soldiers were killed; the French lost fifty-eight of their military. The Islamic Jihad took responsibility for the bombings on that occasion. In December 1983 a truck filled with gas cylinders and explosives rammed into the three-story administrative wing of the U.S. embassy in Kuwait City, killing five people. This attack was undertaken by a Shi’ite Islamic group with ties to Iran.

In Africa terrorists had been training to undertake attacks against Western interests, which included the bombing of the Norfolk Hotel in Nairobi, Kenya in December 1980; attacks on U.S. military troops in Mogadishu, Somalia in October 1993; bombing the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in August 1998; bombing the USS Cole destroyer in the harbor of Aden, Yemen in October 2000; bombing the Paradise Hotel in Mombasa, Kenya in November 2002. After the U.S. embassy bombings journalist Charles Cobb Jr., wrote, “The large number of Africans reflects the continent’s fertility as a recruiting ground for the radical Islamist movements that, some believe, have emerged due to the failures of post-colonial African governments to provide adequate education systems and healthy economies.” In the disastrous attacks on September 11, 2001 against the United States, twelve of the twenty-two terrorists came from African countries. On October 10, 2001 allAfrica.com reported that seven of the terrorists came from Egypt, two from Kenya; one each from Libya, Zanzibar, and Comoros.

In May 2003, while serving as U.S. Ambassador to Mauritius, I received a report that three Western residential complexes in eastern Riyadh, Saudi Arabia had been attacked by al-Qaeda terrorists. According to diplomatic security sources, there had been many warnings of this attack, and a nearby “safe house” filled with munitions was uncovered in a raid. Even after that, no additional precautions reportedly were taken. As a result thirty-six people, including ten Americans were killed in the attack.

There were many signs of al-Qaeda’s presence in the Horn of Africa and East Africa, while Osama bin Laden was in Sudan from 1991 to 1996. The State Department could have readily made embassy assessments to determine that they were adequately protected, had appropriate setbacks, and perimeter separation; able to withstand the shock of a high-level earthquake. We had enough warning and knowledge from the prior embassy bombings to upgrade and protect, or replace every embassy in Africa and elsewhere. Also no embassy should have been located in a multi-tenant building, as we were on the fourth floor, adjacent to a busy street. Some of our embassies were in strategic locations, while others were in more dangerous conflicted areas. All embassies needed to operate in a secure environment, with American trained personnel protecting our diplomats at the embassy, at home, and while carrying out bilateral relations in the host country. This should have been part of a master plan once expansion began around the world after World War II.

At the end of the Cold War in the 1980s, the U.S. focused more of its attention on the Eastern Bloc countries, and very rapidly built over a dozen new embassies there, although the real threat to U.S. security was in Africa. The increased presence of al-Qaeda and radical Islamists in Africa since the early 1990s was alarming. Radical Islamists were gaining support in the populous, poverty-stricken Muslim countries. The U.S. embassy closures in Africa in the 1990s increased our exposure to global terrorism, with al-Qaeda recruiting and training in the Horn of Africa and East Africa, and spreading to other parts of the continent.

In 1996 U.S. Ambassador Prudence Bushnell had sent cables to the State Department regarding the lack of security at the U.S. embassy in Nairobi. An official felt the ambassador was overreacting. A security team was sent to inspect the embassy and reported that it met their standards for a medium-threat facility. General Anthony Zinni visited the embassy in early 1998 and reported there were significant risks, and that the embassy would be an easy target for terrorists. The State Department felt no security upgrades were necessary. The U.S. embassy in Dar es Salaam was no better protected from potential attacks. The world knows what happened on August 7, 1998, with the terrorist bombings of both embassies, in which 224 people died. Why didn’t the State Department take these warnings more seriously? Why was Congress so shortsighted that it did not protect our overseas operations by providing adequate funding? Why were U.S. intelligence sources so naive in their belief that sub-Saharan Africa did not have a well-organized al-Qaeda network? These attacks were planned while Osama bin Laden was next door in Sudan. The attacks could have been avoided with a more consistent engagement of the countries in the Horn of Africa and East Africa as far back as the early 1990s.

We are living in the most crucial time in modern history since the Cold War. At least then we could see our enemy, which is no longer the case. Today’s enemy has no name, no face, no uniform, and not even a standing army. Their mission is to control the world under Sharia, the brutal Islamic law; take the world back to the time in the twelfth century when Islam controlled vast regions of North Africa and the Middle East. Al-Qaeda and other radical Islamic groups are bent on destroying Western culture-- particularly the United States. They will attack U.S. interests at every juncture possible. In the recent attacks in Benghazi there were signs reading, “America has long been an enemy to Islam”, and “Death to America”, which tell a chilling story.

The State Department, reportedly, did not provide adequate cover for Ambassador Chris Stevens and the other three embassy officials who were killed. The U.S. Consulate in Benghazi did not meet minimum security standards for such a facility in a conflicted area. Our intelligence leading up to the unrest that was unfolding was faulty. In addition had there been adequate U.S. security protection after the initial attack, instead of depending on local contract officers, the diplomats could have been saved. The U.S embassy also has a full time regional security officer (RSO), who oversees surveillance detection units, the “eyes and ears” around our missions. The RSO’s role is to make sure there is adequate security at the embassy, consulates, and residences; undertake counter-surveillance measures. Based on reports, we depended too much on the host country government security forces and private security contractors for protection. The disastrous results could have been prevented, had we followed established diplomatic security standards. Instead history has repeated itself —we did not protect our diplomats operating in harm’s way.

The State Department, reportedly, did not provide adequate cover for Ambassador Chris Stevens and the other three embassy officials who were killed. The U.S. Consulate in Benghazi did not meet minimum security standards for such a facility in a conflicted area. Our intelligence leading up to the unrest that was unfolding was faulty. In addition had there been adequate U.S. security protection after the initial attack, instead of depending on local contract officers, the diplomats could have been saved. The U.S embassy also has a full time regional security officer (RSO), who oversees surveillance detection units, the “eyes and ears” around our missions. The RSO’s role is to make sure there is adequate security at the embassy, consulates, and residences; undertake counter-surveillance measures. Based on reports, we depended too much on the host country government security forces and private security contractors for protection. The disastrous results could have been prevented, had we followed established diplomatic security standards. Instead history has repeated itself —we did not protect our diplomats operating in harm’s way.