Note these excerpts regarding the death of Fazul Abdullah Mohammed last June:

"Top Al Qaeda Operative Killed in Somalia, Officials Say"

By the CNN Wire Staff

June 11, 2011 — Updated 2219 GMT (0619 HKT)

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called Mohammed’s death “a significant blow to al Qaeda, its extremist allies and its operations in East Africa. (Read the full story on cnn.com)

Somali officials confirmed today that Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, al Qaeda’s leader in East Africa and a senior Shabaab commander, was killed at a Somali military checkpoint in Mogadishu earlier this week. Fazul is one of the most wanted terrorists in East Africa for his role in attacks on US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania as well as his role within Shabaab. (Read the full story on longwarjournal.org)

The report’s authors pointed out that “… the “account of his killing did not sit well with people who knew Fazul’s history as a crafty and skilled operational commander. Recently, scholar Nelly Lahoud postulated that Fazul, who was close to Osama Bin Laden and vocally opposed to a merger between Al Qaeda and Al Shabaab, may have instead been killed as part of a plot by…”

Media coverage of the recent killing of the legendary terrorist, Fazul Abdullah Mohammed has been extensive. I had tracked Fazul’s whereabouts while serving as U.S. ambassador to the island nation of the Union of the Comoros from 2002 to 2005. I discuss this extensively in my book, “When the White House Calls”.

After almost thirteen years of evading capture Fazul was killed on June 8, 2011 in the backyard of where he trained so many young followers. During this period of time Fazul created considerable havoc, with many people losing their lives. With the number of articles published about Fazul, since his death, I wondered how many of the writers had spent a day in Comoros. Our embassy staff had spent considerable time in Comoros gathering information on Fazul. Since he is not a household name, I want to share some insights into Fazul’s background and segments of his conflicted life.

Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, known also as Haroun Fazul among a long list of aliases, was indoctrinated in madrassas and became a radical jihadist. The Horn of Africa and East Africa region became his sanctuary. Born in Comoros, Fazul has been identified as the mastermind responsible for attacks against two embassies, a resort hotel, and an airliner. He had also been implicated in efforts to smuggle and sell blood diamonds from the West African country of Sierra Leone, the proceeds of which were believed to have been a major source of funding for the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Fazul had become the leader of al-Qaeda in East Africa and later the Somalia based al-Shabaab youth organization.

The United States had had many warnings from the Comoros government that large numbers of foreigners and radical Islamic clerics were traveling to and from the Comoros islands in the 1990′s. While U.S. ambassador, I met with various government, business and Muslim leaders; and people with non-governmental organizations, to acquaint myself with the potential threats from the influx of these strangers.

Like many young children Fazul attended madrassas (Koranic schools), which received little oversight from the government. Fazul was recruited by Islamic imams (preachers), while attending one of these schools in his hometown of Moroni, to study in Pakistan. Ostensibly his family sent him there to study computer science, but ultimately he made his way to Afghanistan to train with Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda. Fazul then went to Kenya with occasional trips to Tanzania, Sudan and Somalia to help train and establish terrorist cells in the Horn of Africa and East Africa. “Fazul had become a top aide of Osama bin Laden”.

Fazul planned the August 7, 1998 bombings of the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi, Kenya and the U.S. Embassy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He was also responsible for the November 28, 2002 bombing of the Israeli-owned Paradise Hotel in Kikambala, a beach resort fifteen miles north of Mombasa in southeastern Kenya; and the attempted surface-to-air missile attack on a Boeing 757 operated by the Israeli-owned charter company Arkia as it was leaving Mombasa.

Fazul had returned to Comoros on August 14, 1998, a week after the embassy bombings to hide out with his family. He could have been easily captured, since the government of Comoros invited the FBI to come to the island to apprehend him. By the time the FBI finally responded three weeks later Fazul had already fled the country.

A slightly built man trained as an explosives expert Fazul eluded capture by being a disguise expert, sometimes masquerading as a woman. Between 2000 and 2001, a local judge in Moroni assigned to the Fazul case gleaned information that Fazul was periodically speaking to his wife Halima on a neighbor’s telephone. With no structure put in place by the United States for intelligence gathering, this critical information did not reach the right ears. If we had had an active diplomatic presence in Comoros at the time, the FBI and other agencies could have taken effective action, possibly leading to the capture of Fazul. However our embassy there was closed in 1993, as the area had little interest to the United States. The State Department and other agencies also did not believe there were any infiltration concerns with terrorist groups in Comoros.

On March 20, 2003, a cable arrived at our embassy in Mauritius from the regional security officer at the U.S. Embassy in Antananarivo, alleging among other things, that al-Qaeda operatives were moving through Comoros and Seychelles. As many as two hundred foreigners were in Comoros, including a large number in Mohoro, a small village on Grande Comore. They were reported to be staying at the mosques and madrassas recently established by the rogue Saudi charity al-Haramain. I had known about some of the activities at the mosques and madrassas from several sources. Now, this cable from a nearby embassy validated these reports. “I wondered whether Fazul might be one of the infiltrators”.

Information about Fazul’s whereabouts had reached me on several occasions. We passed along to Washington data about Fazul’s plans to travel to Comoros for a family visit, to come to the country for a family funeral, and visits to Mahajanga, a town of ninety thousand Comorians, located on the northwest coast of Madagascar, a few hours by boat from the Comoros Islands. From various sources we learned Fazul had another wife in this town (and in February 2007, the local newspaper ‘Midi Madagasikara’ reported that Fazul had been seen there). On another occasion we reported that a watch salesman was coming from Pakistan to Moroni to deliver a message from Fazul to his family, and we included an itinerary and the flights he would be taking. Some of this information might have presented an opportunity to capture Fazul. When we forwarded any of this information on to Washington it was not considered credible. The people we informed did not believe Fazul traveled to Comoros to visit his family. Thus they did not follow up on any of our leads.

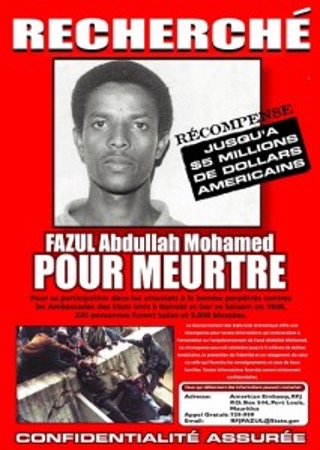

Wanted poster for Fazul Abdullah Mohammed Issued by the Rewards for Justice Program I believed differently, and pressed the embassy’s regional security officer to obtain funding from the Bureau of Diplomatic Security for instituting the Rewards for Justice Program. The bureau agreed to pay for the printing of large posters with Fazul’s picture and a photo taken of the bombed embassies set against a bright red background to draw attention. We attached a large number of these posters to telephone poles and placed many inside shop windows around Grand Comore. We also distributed thousands of matchbooks with Fazul’s picture on the cover. Boldly printed in black letters was the information that a $5 million reward would be given for information leading to his capture. Candidly, I would have offered twice that amount if I thought we would get the Comorians attention. I knew they were a close-knit Arab Muslim society, and for them to consider turning in Fazul, it might take a higher amount as an inducement. Also, Comorians expressed skepticism that the United States would actually pay this amount to anyone.

Wanted poster for Fazul Abdullah Mohammed Issued by the Rewards for Justice Program I believed differently, and pressed the embassy’s regional security officer to obtain funding from the Bureau of Diplomatic Security for instituting the Rewards for Justice Program. The bureau agreed to pay for the printing of large posters with Fazul’s picture and a photo taken of the bombed embassies set against a bright red background to draw attention. We attached a large number of these posters to telephone poles and placed many inside shop windows around Grand Comore. We also distributed thousands of matchbooks with Fazul’s picture on the cover. Boldly printed in black letters was the information that a $5 million reward would be given for information leading to his capture. Candidly, I would have offered twice that amount if I thought we would get the Comorians attention. I knew they were a close-knit Arab Muslim society, and for them to consider turning in Fazul, it might take a higher amount as an inducement. Also, Comorians expressed skepticism that the United States would actually pay this amount to anyone.

The United States really needed to maintain a constant presence in Comoros and work with the Comorians to build a relationship of trust, as this was the only answer in the long run. Dealing long distance by telephone would lead to a less than desirable result. Also, there were many Comorians living along the east coast of Africa and on the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba. Some of these people could possibly have been recruited to track Fazul and lead us to him. It would have been a smart idea to have some money ready in exchange for information, as a good-faith gesture. The bottom line was that we needed to have an active presence throughout the region if we were going to develop friends and build a lasting trust. But this did not seem to be a priority for the United States.

Under the Rewards for Justice Program, we received an anonymous email from a Comorian source saying that a particular person, a Pakistani, was departing Comoros on the following Sunday en route to Pakistan to make contact with Fazul. We were told that this individual sold cellphones, tapes, cassettes, watches and so on, and traveled to Comoros every three weeks, possibly carrying correspondence between Fazul and family members. The source also commented that various people from Madagascar frequently met with the Pakistani in Comoros. On one occasion the source noted, the Pakistani had said Fazul was in Pakistan in an area where he wouldn’t have any problems. We passed this information along to Washington, but never heard back from anyone.

It was also reported that Fazul had spent considerable time in Lamu, Kenya, and in an al-Qaeda training camp near Ras Kamboni in southern Somalia, where U.S. aircraft attacked some Islamist militia and al-Qaeda fighters on January 7-9, 2007. Fazul’s wife Halima and their three children were captured on January 9, 2007, in the town of Kiunga near Lamu in Kenya, only a few miles from the Somalia border. They were held for questioning and spent four months incarcerated in Kenya and Ethiopia. Released on May 4, 2007, they returned to Comoros. Apparently they had spent considerable time in Pakistan, probably with Fazul, since their children spoke English fluently with a Pakistani accent.

Fazul had escaped capture in Comoros leaving on August 22, 1998, with reports indicating he went to Pakistan. His wife claimed she divorced him and went to Mahajanga on the northwest coast of Madagascar, where she supposedly married a Pakistani, giving her a way of escaping as well. She reappeared in Kenya in January 2007. In reality she never divorced Fazul. However reportedly, he had taken a second wife from the town of Mahajanga, (although a report said she was from the island of Pate off the coast of Kenya, near Lamu, which Fazul had used as a safe haven).

My concern was for the young students in Comoros attending the madrassas, and echoed in a July 14, 2007 Economist article “An Unusual Haunt for al-Qaeda”, in which it was reported that some Comorians resent the arrival of conservative Pakistanis intent on teaching the Koran in villages. “They’re hiding something” said Soihili Ahmed, editor of Al Watwan the local newspaper. “A group of them has set up in a historic mosque in Ntsaoueni, in the north of Grand Comore. The bearded Pakistanis deliver a stern but polite message. Sitting cross-legged on a dusty carpet, brewing tea and eating nuts and sweets brought with them from Karachi, they say the Comorians should return to Taliban-style rule. A few of the listeners are Comorian boys. Wild-eyed, speaking alternately with gentleness and religious certitude, could they resemble Mr. Fazul at the start of his journey?”

During one of my visits to Comoros I met with a government official regarding the offshore educational opportunities the imams offered young Comorians. Many young men who were offered scholarships to study overseas had come back with radical Islamic beliefs and in some cases had become quite militant; others had simply not returned at all. To indicate how out of control the situation was becoming the official provided me with a list of some nine hundred students who recently had gone abroad under these programs.

On April 14, 2008, I read a Center for Strategic and International Studies article “Comoros: Big Troubles on Some Small Islands” written by Matthew B. Dwyer, a former Peace Corps volunteer who served in Comoros in the 1990s, and taught at the International School of Luxembourg. “The United States has a clear interest in preventing the Comoros from becoming an attractive place of refuge for wanted terrorists such as Fazul” Dwyer wrote, and that “The Comorian government is on record as being eager to cooperate with U.S. and UN anti-terrorist efforts. Unfortunately, this cooperative attitude has gone unappreciated”. He added “There is an International Military Education and Training (IMET) program in Comoros, budgeted at just $95,000 in 2008, but this is the only U.S. assistance the country receives”. Dwyer did not embellish the situation that exists in this destitute Muslim country. I could not understand why the State Department had not taken more of an interest there. In fact no State Department personnel had engaged Comoros more actively than the Peace Corps volunteers who worked there in the 1990s. Dwyer summarized the concerns I had expressed to Washington in a number of consultations, about our need to have a permanent U.S. presence there. “In the Comoros” Dwyer concluded, “the United States has committed only sins of omission. This must change, and the first step should be the reinstatement of the U.S. Embassy to the Union of the Comoros. It is no coincidence that the most peaceful period of Comorian independence coincides with the presence of a full U.S. diplomatic mission in the islands. It is time for Comorian[s] to once again be able to count the United States as a friend”.

In December 2009, a Comorian government leader recounted for me a chance meeting with a former classmate of Fazul, who recalled how he had been considered a very crafty teenager. This person said that when Fazul was thirteen or fourteen years old he constructed a homemade bomb and detonated it in front of his friends. No one stopped him. After the embassy bombings in 1998, he returned to Comoros and visited the same school in Moroni, where his brother was a teacher. The former classmate ran into Fazul there, but at first did not recognize him. Shortly thereafter Fazul left the country. At the time, no one in Moroni knew he had had anything to do with the bombings. Days later the FBI came to the island, and even then no one knew who or what they were pursuing until sometime later. The FBI missed their opportunity to catch Fazul while he was there. If the United States had had an active presence on the island, we might have been able to glean from the clues Fazul left behind. We could have been the conduit between the FBI and the Comorians to capture him before he did any more damage.

During the conversation with the government leader, he shared with me information about Fazul’s wife Halima who that year had received a new electronic-type passport (an e-passport) from the Comorian Department of National Security. The government of Comoros had not stopped the issuance of the passport. The United States also took no action. It had not advised the Comorian government to watch her movements, or prevent her from getting such a passport which would open the world to her.

Thereafter Halima flew to Anjouan, then sailed to Mahajanga and went on to Antananarivo in Madagascar. There she boarded a plane to Nairobi, Kenya. Crossing the porous border she went into Somalia. Her purpose was to be present at the installation ceremony of her husband Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, who was to become the new leader of Somalia’s al-Shabaab organization. “Nobody followed her. No one checked the sources of money affording her the opportunity to make this trip”.

Al-Shabaab is the outgrowth of the Islamic Courts Union, after they lost power in their fight with Ethiopian forces in 2006. This jihadist group is intent on starting a holy war against Christians in Ethiopia, the Somali Transitional Federal Government (TFG), the African Union (AU) and United Nations (UN) peacekeepers, and western NGOs on humanitarian missions. Under Fazul’s leadership terrorist activities included the use of car bombs, suicide attacks, road mines, and other disruptive bomb attacks in densely populated areas. Daily we were aware of the destruction al-Shabaab was causing in Somalia, Uganda, and in other countries. Al-Shabaab was also actively recruiting young Somalis, many from the United States and elsewhere. Hence we could expect more attacks, possibly reaching our soil in the near future.

In the hunt for terrorist leaders, Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, weaned on radical Islamic indoctrination, and once considered a man of no consequence by our government, had risen in the ranks of violence and inhumanity. As the new leader of the growing al- Shabaab terrorist organization in Somalia he could no longer be ignored.

On that fateful night of June 8, 2011, the al-Shabaab and al-Qaeda organizations both had a major setback. Fazul traveling from South Africa to Somalia was met by a trusted al-Shabaab lieutenant at a border crossing. Returning to an al-Shabaab controlled section of Mogadishu, at a checkpoint they ran into AU and TFG military troops. In the ensuing fire-fight Fazul and his associate were killed. At the time Fazul was carrying several computers, cellphones, a number of passports and $40,000 in cash, apparently for another planned mission.

The world is safer by his demise, but with Fazul’s capture it could have been an opportunity to find out more about this young man, who was indoctrinated in Koranic schools, and turned out to be one of the most notorious radical Islamists. I had planned to interview this most wanted terrorist, to better understand why he chose the path of “armed jihadism”.

Fazul’s mentor, Osama bin Laden built an extensive radical Islamic network, which will continue in its fanatical quest to take the world back to the time in the twelfth century when Sultan Saladin controlled vast regions of northern Africa and the Middle East. Osama bin Laden had consistently stated “That he considered all non-Muslims infidels and invaders of Muslim soil”. He had called for a global jihad against all the Western powers, with the United States being foremost on the list.

Radical Islamic leaders will come and go, but the fundamentalist Islamic movement, which encourages an armed jihad around the world, will continue under new leadership.